FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act

The Trump Administration’s initial FY2018 budget request, released on May 23, 2017, included a total of $677.1 billion for the national defense budget function (Budget Function 050), which encompasses all defense-related activities of the federal government. Of that amount, $659.8 billion was for appropriation accounts for which authorization is provided in the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The remainder of the request was either for mandatory funds not requiring annual authorization or for discretionary funds outside the scope of the NDAA.

That initial Administration request included $595.3 billion in discretionary funding for the so-called base budget, that is, funds intended to pay for activities that the Department of Defense (DOD) and other national defense-related agencies would pursue even if U.S. forces were not engaged in contingency operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. The remaining $64.6 billion of the request, formally designated as funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), would fund the incremental cost of those ongoing operations as well as any other DOD costs that Congress and the President agree to so designate.

On July 14, 2017, the House passed by a vote of 344-81 H.R. 2810, the version of the FY2018 NDAA that had been reported by the House Armed Services Committee. That bill would have authorized $613.8 billion for the base budget—$18.5 billion more than the Administration’s initial request—and $74.6 billion designated as OCO funding, which is $10 billion more than the Administration’s OCO request.

The Senate passed its version of H.R. 2810 on September 18, 2017, by a vote of 89-8, after first replacing the House-passed text of that bill with the text of S. 1519, the version of the FY2018 NDAA that had been reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee. This Senate-passed version of the bill would have authorized $631.9 billion for the base budget—exceeding the base budget request by nearly $37 billion—and $60.0 billion for OCO-designated funding.

In November 2017—after the House and Senate had passed their respective versions of the FY2018 NDAA but before conferees had completed negotiations to produce a compromise version of the bill—the Trump Administration amended its FY2018 DOD budget request, asking for an additional $5.9 billion. The additional funds included $4.0 billion for missile defense-related programs the Administration described as being in response to recent missile tests and other activities by North Korea. The budget amendment also included $674 million to repair two Navy destroyers damaged in collisions and $1.2 billion to support the President’s decision to increase by approximately 3,500 the number of U.S. military personnel in and around Afghanistan. The $1.2 billion associated with the Afghanistan troop levels was designated as OCO while the remaining $4.7 billion of the increase was included in the base budget.

The final version of H.R. 2810 authorized $626.4 billion for base budget activities and $65.7 billion for OCO-designated funding. The House agreed to this final version of the bill on November 14, 2017, by a vote of 356-70. The Senate agreed to it on November 16, 2017, by voice vote. President Trump signed the bill into law (P.L. 115-91) on December 12, 2017.

Congressional action on FY2018 defense funding reflected a running debate about the size of the defense budget given the strategic environment and budgetary issues facing the United States. Annual limits (often referred to as caps) on discretionary spending for defense and for nondefense federal activities, set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), remain in place through FY2021. If the amount appropriated for either category were to exceed the relevant cap, it would trigger near-across-the-board reductions to a level allowed by the cap—a process called sequestration. Appropriations designated by Congress and the President as funding for OCO or for emergencies are exempt from these caps.

For the period during which Congress was considering the FY2018 NDAA, the BCA limit on discretionary defense spending was $549 billion. The caps apply to appropriations, not authorization legislation. However, if Congress had appropriated for national defense programs the amounts requested by the Administration or the amounts authorized by any of the versions of H.R. 2810 passed by House or Senate, those appropriations would have triggered sequestration.

Before Congress enacted any FY2018 appropriations bills, it raised the FY2018 and FY2019 discretionary spending caps on defense and nondefense spending as part of P.L. 115-123, which included the fifth continuing appropriations resolution for FY2018. The revised cap on base budget, discretionary defense appropriations for FY2018 is $629 billion, which would accommodate appropriations to the level authorized by the enacted version of H.R. 2810.

FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- Budgetary Context

- Budget Caps and the FY2018 NDAA

- FY2018 Defense Budget Request and NDAA

- House and Senate Action on FY2018 NDAA

- FY2018 DOD Budget Amendment (November 2017)

- FY2018 NDAA Conference Report (H.R. 2810)

- Selected Budget and Policy Issues in H.R. 2810

- Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty

- Countering Russia

- North Korean Threats

- Prohibitions on Transfer or Release of Detainees

- Selected DOD Cyber Matters

- Selected Government-Wide Information Technology Matters

- Software Security Issues

- Military Personnel Matters

- Strategic Nuclear Forces

- Ballistic Missile Defense Programs

- Space and Space-Based Programs and Activities

- Overview of Ground Vehicle Programs

- Overview of Shipbuilding Programs

- Selected Aviation Programs

- Acquisition Reform

- Military Construction

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Administration Proposed Discretionary Limits: FY2018-FY2027

- Table 2. FY2018 NDAA (H.R. 2810/S. 1519)

- Table 3. FY2018 Military End-Strength

- Table 4. Selected Strategic Offense and Long-range Strike Systems

- Table 5. Selected Missile Defense Programs

- Table 6. Selected Military Space Systems

- Table 7. Selected Ground Combat Systems and Tactical Vehicles

- Table 8. Selected Shipbuilding and Modernization Programs: Combatant Ships

- Table 9. Selected Shipbuilding Programs: Support and Amphibious Assault Ships

- Table 10. Selected Fighter and Attack Aircraft Programs

- Table 11. Selected Tanker, Cargo, and Transport Aircraft Programs

- Table 12. Selected Patrol and Surveillance Aircraft Programs

- Table 13. Selected Helicopter and Tilt-Rotor Aircraft Programs

- Table 14. Authorization for Military Construction and Family Housing Activities

Summary

The Trump Administration's initial FY2018 budget request, released on May 23, 2017, included a total of $677.1 billion for the national defense budget function (Budget Function 050), which encompasses all defense-related activities of the federal government. Of that amount, $659.8 billion was for appropriation accounts for which authorization is provided in the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The remainder of the request was either for mandatory funds not requiring annual authorization or for discretionary funds outside the scope of the NDAA.

That initial Administration request included $595.3 billion in discretionary funding for the so-called base budget, that is, funds intended to pay for activities that the Department of Defense (DOD) and other national defense-related agencies would pursue even if U.S. forces were not engaged in contingency operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. The remaining $64.6 billion of the request, formally designated as funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), would fund the incremental cost of those ongoing operations as well as any other DOD costs that Congress and the President agree to so designate.

On July 14, 2017, the House passed by a vote of 344-81 H.R. 2810, the version of the FY2018 NDAA that had been reported by the House Armed Services Committee. That bill would have authorized $613.8 billion for the base budget—$18.5 billion more than the Administration's initial request—and $74.6 billion designated as OCO funding, which is $10 billion more than the Administration's OCO request.

The Senate passed its version of H.R. 2810 on September 18, 2017, by a vote of 89-8, after first replacing the House-passed text of that bill with the text of S. 1519, the version of the FY2018 NDAA that had been reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee. This Senate-passed version of the bill would have authorized $631.9 billion for the base budget—exceeding the base budget request by nearly $37 billion—and $60.0 billion for OCO-designated funding.

In November 2017—after the House and Senate had passed their respective versions of the FY2018 NDAA but before conferees had completed negotiations to produce a compromise version of the bill—the Trump Administration amended its FY2018 DOD budget request, asking for an additional $5.9 billion. The additional funds included $4.0 billion for missile defense-related programs the Administration described as being in response to recent missile tests and other activities by North Korea. The budget amendment also included $674 million to repair two Navy destroyers damaged in collisions and $1.2 billion to support the President's decision to increase by approximately 3,500 the number of U.S. military personnel in and around Afghanistan. The $1.2 billion associated with the Afghanistan troop levels was designated as OCO while the remaining $4.7 billion of the increase was included in the base budget.

The final version of H.R. 2810 authorized $626.4 billion for base budget activities and $65.7 billion for OCO-designated funding. The House agreed to this final version of the bill on November 14, 2017, by a vote of 356-70. The Senate agreed to it on November 16, 2017, by voice vote. President Trump signed the bill into law (P.L. 115-91) on December 12, 2017.

Congressional action on FY2018 defense funding reflected a running debate about the size of the defense budget given the strategic environment and budgetary issues facing the United States. Annual limits (often referred to as caps) on discretionary spending for defense and for nondefense federal activities, set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), remain in place through FY2021. If the amount appropriated for either category were to exceed the relevant cap, it would trigger near-across-the-board reductions to a level allowed by the cap—a process called sequestration. Appropriations designated by Congress and the President as funding for OCO or for emergencies are exempt from these caps.

For the period during which Congress was considering the FY2018 NDAA, the BCA limit on discretionary defense spending was $549 billion. The caps apply to appropriations, not authorization legislation. However, if Congress had appropriated for national defense programs the amounts requested by the Administration or the amounts authorized by any of the versions of H.R. 2810 passed by House or Senate, those appropriations would have triggered sequestration.

Before Congress enacted any FY2018 appropriations bills, it raised the FY2018 and FY2019 discretionary spending caps on defense and nondefense spending as part of P.L. 115-123, which included the fifth continuing appropriations resolution for FY2018. The revised cap on base budget, discretionary defense appropriations for FY2018 is $629 billion, which would accommodate appropriations to the level authorized by the enacted version of H.R. 2810.

Background

The annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) provides authorization of appropriations for the Department of Defense (DOD), defense-related atomic energy programs of the Department of Energy, and defense-related activities of other federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In addition to authorizing appropriations, the NDAA establishes defense policies and restrictions, and addresses organizational administrative matters related to DOD.1 Unlike an appropriations bill, the NDAA does not provide budget authority for government activities.

|

FY2018 NDAA: Keeping the Numbers Straight Although the House and Senate each passed an FY2018 NDAA designated H.R. 2810, there were hundreds of differences between the two versions. Initially, H.R. 2810 was reported by the House Armed Services Committee and then was debated and amended on the floor of the House before the House passed it on July 14, 2017. The version of the FY2018 NDAA reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee was designated S. 1519. When the Senate began consideration of the NDAA, it called up the House passed bill (H.R. 2810) amended it by striking the text and substituting a modified version of S. 1519—the Senate committee-reported bill. In this report, the versions of H.R. 2810 passed by the House and Senate will be referred to as the House bill and Senate bill, respectively. The version of H.R. 2810 reported by the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) and S. 1519 as reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) will be referred to as the HASC version and the SASC version, respectively. |

Congressional action on the FY2018 NDAA reflected a running debate about the size of the defense budget given the strategic environment and budgetary issues facing the United States. Annual limits on discretionary spending set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) remain in place through FY2021 and fundamentally shape congressional actions related to all federal spending, including defense funding.2

Constrained by these limits, Congress and the executive branch face an increasingly complex and unpredictable international security environment, evidenced by a variety of threats to U.S. security interests including

- action around the globe by nonstate, violent extremist organizations—such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Al Qaeda;

- Russian-backed proxy warfare in Ukraine;

- North Korean provocation evidenced by an "unprecedented" number of missile test launches and its "use of malicious cyber tools" to threaten and destabilize the region;3

- China's expansion of its nuclear enterprise, its investments in power projection and continued island building in the South China Sea; and

- Iran's continued efforts to support international terrorist organizations and establish regional dominance.4

Congress completed action on the FY2018 NDAA before the Trump Administration completed its initial updates of the National Defense Strategy and National Security Strategy. A Nuclear Posture Review also was in progress when the bill was enacted. Thus, to some degree, the Trump Administration's initial FY2018 budget request served as a placeholder while Congress awaited completion of these major strategic assessments.5

One exception to that rule is that the Administration's November 2017 amendment to its FY2018 budget request reflected its revision of U.S. strategy in Afghanistan: The additional $5.9 billion requested included $1.2 billion to support the President's decision to deploy in Afghanistan about 3,500 more U.S. personnel than the May 2017 budget request had assumed.6 Although the additional funds were requested after the House and Senate each had passed their respective versions of the NDAA, conferees incorporated the requested amounts into the version of the bill that was enacted.

|

Organization of this Report Congressional action on the FY2018 NDAA took place in the context of a complicated and atypical sequence of events driven by three factors: the ongoing budget debate; the unsettled state of the new Administration's policies when the FY2018 budget request was submitted to Congress; and bellicose statements and actions by the government of North Korea. This report will address aspects of the bill and its context in the following order:

|

Budgetary Context

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA/P.L. 112-25), enacted August 2, 2011, contains several measures intended to reduce the budget deficit by $2.1 trillion over the period FY2012-FY2021. Toward that goal, the legislation established annual limits that would reduce discretionary spending by approximately $1.0 trillion, compared with projected spending over that period.

The BCA established separate limits (commonly referred to as caps) on defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority that are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration.7 Sequestration provides for the automatic cancellation of previously appropriated spending to reduce discretionary spending to the limits specified in the BCA. The defense limit applies to the national defense budget (function 050), but does not restrict amounts designated by the President and Congress as funding for emergencies or for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO).8

|

The Budget Control Act For additional information on the BCA, see CRS Report R44039, The Budget Control Act and the Defense Budget: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|

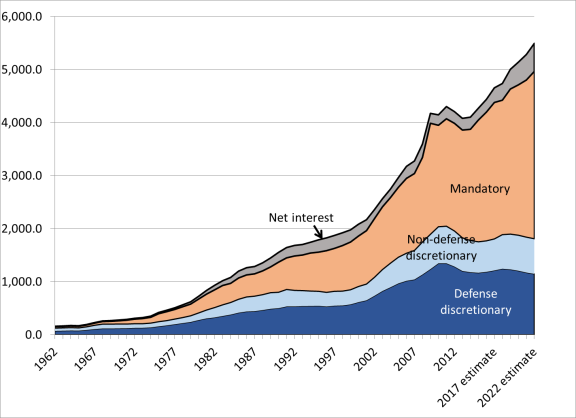

Figure 1. Federal Outlays by Budget Category amounts in billions of dollars |

|

|

Source: OMB Historical Table 8.1. |

Over the nearly six decades from 1962 through 2022, OMB projects that defense outlays would increase from $52.6 billion to a projected $662.3 billion. Over the same period, net9 mandatory spending is projected to increase at roughly 10 times that rate (from $27.9 billion to $3.16 trillion). (See Figure 1.)

According to OMB data, defense outlays, which accounted for 49.2% of federal spending in 1962, had dropped to 19.4% in 2011—the year the BCA was enacted—and are projected to drop to 13.7% by 2022. On the other hand, net mandatory outlays combined with net interest on the national debt, which accounted for 32.5% of outlays in 1962 and 62.6% in 2011, are projected to account for 76.2% of outlays in 2022. (See Figure 2.)

Similarly, the defense share of the GDP has declined relatively steadily since 1962, while the share of the GDP consumed by mandatory spending and net interest has risen. (See Figure 3.)

|

|

|

||||||

|

Trends in Federal Spending For information on federal deficits and debt, see CRS Report R44383, Deficits and Debt: Economic Effects and Other Issues, by [author name scrubbed]. For additional information on mandatory spending, see CRS Report R44641, Trends in Mandatory Spending: In Brief, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||

Budget Caps and the FY2018 NDAA

During the period in which Congress was deliberating on the FY2018 NDAA, the BCA limit (or cap) on FY2018 discretionary spending for national defense (budget function 050) was $549 billion. The Trump Administration proposed $603 billion for base budget national defense discretionary spending in FY2018—$54 billion more than the BCA cap. In the absence of the appropriate statutory changes to BCA, defense appropriations at the requested level would have triggered sequestration.10

The Trump Administration's FY2018 budget called on Congress to raise the defense discretionary caps for FY2018 and subsequent years to accommodate proposed defense budget increases in FY2018 and beyond.11 This proposal was coupled with a recommendation to continue BCA-like limits on nondefense discretionary spending through FY2027—six years beyond the expiration of the Budget Control Act (see Table 1).

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

2026 |

2027 |

|

|

Current BCA Limits |

||||||||||

|

Defense |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

― |

― |

― |

― |

― |

― |

|

Nondefense |

516 |

530 |

543 |

556 |

― |

― |

― |

― |

― |

― |

|

Proposed Limits |

||||||||||

|

Defense |

603 |

616 |

629 |

642 |

655 |

669 |

683 |

697 |

712 |

727 |

|

Nondefense |

462 |

453 |

444 |

435 |

426 |

417 |

409 |

401 |

393 |

385 |

Source: Office of Management and Budget, A New Foundation for American Greatness—President's Budget FY 2018, Table S-7.

Under the Administration's proposal, projected defense spending increases totaling $463 billion over the period FY2018-FY2027 would be more than offset by reductions in nondefense spending that would total $1.5 trillion over the same period. All told, the President's budget plan proposed a $1 trillion reduction in federal discretionary spending.12

The House and Senate disregarded the defense spending cap in passing their respective versions of the FY2018 NDAA and in agreeing to the conference report on a final version of the measure. All versions of the bill (H.R. 2810) authorized defense appropriations at levels which, if enacted, would have exceeded the cap then in force, thus triggering sequestration.

After the FY2018 NDAA was enacted, but before final action on any FY2018 appropriations, the caps on discretionary spending for defense and nondefense programs in FY2018 and FY2019 were increased as part of P.L. 115-123, which included the fifth continuing appropriations resolution for FY2018. The revised cap on base budget, discretionary defense appropriations for FY2018 is $629 billion, which would accommodate appropriations to the level authorized by the enacted version of the FY2018 NDAA.

FY2018 Defense Budget Request and NDAA

Shortly after taking office, President Trump directed Secretary of Defense James Mattis to conduct a "30-day Readiness Review" of "military training, equipment maintenance, munitions, modernization and infrastructure."13 In the wake of that review, DOD moved out along three axes:

- Submitting a detailed amendment to the Obama Administration's FY2017 budget request—seeking an additional $30 billion to address what it described as "immediate and serious readiness challenges;"14

- Developing the FY2018 Budget Request to be "focus[ed] on balancing the program ... while continuing to rebuild readiness;" and

- Beginning formulation of the FY2019-FY2023 Defense Program to be shaped by a new National Defense Strategy and provide "an approach to enchanc[e] the lethality of the joint force against high-end competitors and the effectiveness of our military against a broad spectrum of potential threats."15

In its presentation of the initial FY2018 budget request, DOD highlighted several priorities:

- Improving warfighting readiness;

- "Filling holes" in capacity and lethality while preparing for future growth;

- Reforming DOD business practices;

- Keeping faith with servicemembers and their families; and

- Supporting overseas contingency operations.16

The Trump Administration's initial FY2018 budget request, released on May 23, 2017, included a total of $677.1 billion for national defense-related activities of the federal government (budget function 050).17 Of the national defense total, $667.6 billion was requested for discretionary spending to be provided, for the most part, by the annual appropriations bill drafted by the Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate. The balance—$9.6 billion—was requested for mandatory spending, that is, spending for entitlement programs and certain other payments. Mandatory spending is generally governed by statutory criteria and it is not provided by annual appropriation acts.18

As has been typical in recent years, about 95% of the national defense total, $646.9 billion, is for military activities of the DOD—designated as subfunction 051. The balance of the function 050 request comprises $21.8 billion for defense-related atomic energy activities of the Department of Energy (designated subfunction 053) and $8.4 billion for defense-related activities of other agencies (designated subfunction 054), of which about two-thirds is allocated to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. (See Figure 4.)

Of the initial, $677.1 billion request, $612.5 billion was for the base budget, that is, for funds intended to pay for those activities the DOD and other national defense-related agencies would pursue even if U.S. forces were not engaged in contingency operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. The remainder of the FY2018 request—originally amounting to $64.6 billion—is designated as funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO).

Originally, the OCO designation was assigned to funding associated with post-9/11 military operations in and around Iraq and Afghanistan. However, the range of DOD activities funded as OCO has broadened. The FY2018 OCO request includes $4.8 billion for the European Reassurance Initiative (ERI), a set of actions intended to beef up the U.S. military presence in Europe as a counter to menacing Russian military actions. The Administration's FY2018 request for ERI included $1.7 billion to increase the number of U.S. military personnel in Europe and $2.2 billion to increase prepositioned stocks of U.S. military equipment in the region. The request also included $150 million to "continue train, equip, and advise efforts to build Ukrainian capacity to conduct internal defense operations to defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity."19

One incentive for expanding the range of DOD spending designated as OCO is that, as such, it is exempt from the BCA funding cap.

House and Senate Action on FY2018 NDAA

Of the $667.6 billion in national defense discretionary funding initially requested by the President for FY2018, $659.8 billion fell within the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees and was subject to authorization by the annual National Defense Authorization Act.20

On July 14, 2017, the House passed H.R. 2810, the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2018, by a vote of 344-81. On September 18, 2017, the Senate passed its version of that bill by a vote of 89-8 after having replaced the text of the House bill with an amended version of S. 1519, the version of the bill that had been reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Before passing the NDAA, the Senate modified the committee-reported text, adopting by unanimous consent an amendment incorporating text from more than 100 amendments.21 Subsequently, the Senate adopted an additional 49 amendments, en bloc, by unanimous consent. In the Senate's only roll call vote in relation to an amendment to the NDAA, it voted 61-36 to table (and thus reject) an amendment that would have repealed (six months after enactment of the bill) the joint resolutions on the Authorization of Military Force (AUMF) enacted in 2001 (P.L. 107-40) and in 2002 (P.L. 107-243).22

FY2018 DOD Budget Amendment (November 2017)

In November 2017—after the House and Senate had passed their respective versions of the FY2018 NDAA but before House and Senate conferees had completed work on a compromise version of the bill (H.R. 2810)—the Trump Administration amended its fiscal 2018 budget request, increasing its DOD funding request by a total of $5.87 billion. The requested increase included23

- $4.01 billion to expand and upgrade missile defense programs intended to counter threats from North Korea;

- $674 million to repair USS John S. McCain and USS Fitzgerald, destroyers equipped for antimissile defense that were damaged in separate collisions in the Western Pacific; and

- $1.18 billion to cover costs associated with the deployment in and around Afghanistan of 3,500 more U.S. troops than had been assumed in the FY2018 budget request.

Conferees on the FY2018 NDAA authorized the additional funds requested by the budget amendment.24

The President and Congress designated as emergency funds the $4.7 billion requested for missile defense and ship repair while designating as OCO the funds requested for an enlarged U.S. presence in Afghanistan. Thus, when Congress appropriated those amounts in the FY2018 omnibus appropriations bill, those amounts were exempt from the BCA defense cap.

FY2018 NDAA Conference Report (H.R. 2810)

House and Senate conferees filed a conference report for H.R. 2810 on November 9, 2017. The House agreed to the conference report on November 14, 2017, by a vote of 356-70. The Senate agreed to it on November 16, 2017, by voice vote and the President signed the bill into law (P.L. 115-91) on December 12, 2017. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. FY2018 NDAA (H.R. 2810/S. 1519)

amounts in millions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

|

Title |

Original |

Budget Amendment |

Total Revised Request |

Enacted |

||

|

Missile Defense re: North Korea |

Repair 2 damaged destroyers |

Larger force in Afghanistan |

||||

|

Procurement |

113,983.7 |

2,423.2 |

116,406.9 |

137,311.3 |

||

|

Research, Development, Test and Evaluation |

82,716.6 |

1,346.7 |

84,063.3 |

86,348.7 |

||

|

Operation and Maintenance |

188,570.3 |

42.5 |

673.5 |

189,286.3 |

192,290.0 |

|

|

Military Personnel |

141,686.1 |

141,686.1 |

141,846.4 |

|||

|

Revolving Funds and Other auth. |

37,849.8 |

37,849.8 |

37,676.2 |

|||

|

Military Const. and Fam. Housing |

9,782.5 |

200.0 |

9,982.5 |

9,980.7 |

||

|

Subtotal: DOD Base Budget |

574.589.0 |

4,012.4 |

673.5 |

579,274.8 |

605,453.3 |

|

|

Atomic Energy Defense Activities |

20.477.3 |

20,477.3 |

20,597.8 |

|||

|

Other Non-DOD Activities |

210.0 |

210.0 |

300.0 |

|||

|

Subtotal: Base Budget |

595,276.3 |

599,962.1 |

626,351.1 |

|||

|

OCO |

64,573.0 |

1,184.1 |

65,757.1 |

65,748.3 |

||

|

Grand Total: Base + OCO |

659,849.3 |

4,012.4 |

673.5 |

1,184.1 |

665,719.2 |

692,099.4 |

Sources: Original request is taken from H.Rept. 115-200, Report of the House Armed Services Committee on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA, July 6, 2017. Data on the November 6, 2017, budget amendment are taken from Office of Management and Budget, "Estimate #3, FY2018 Budget Amendments: Department of Defense to support urgent missile defeat and defense enhancements to counter the threat from North Korea, repair damage to U.S. Navy ships, and support the Administration's south Asia strategy," November 6, 2017, accessed at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/DOD_budgetamendment_package_nov2017.pdf. Total revised request is taken from H.Rept. 115-404, conference report on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA.

Note: Conferees on the FY2018 NDAA did not consider a separate budget amendment, also submitted in November 2017, that requested $1.16 billion for repair of DOD facilities damaged by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

|

The original, House-passed version of the FY2018 NDAA would have authorized a total of about $689.0 billion, exceeding the Administration's initial budget request by about $29.2 billion (4.4%). The original Senate-passed version of the bill would have exceeded the initial request by about $32.3 billion or 4.8%. The conference report on H.R. 2810 does not present the authorization levels in the original House and Senate versions in comprehensive detail, and the number and complexity of floor amendments adopted by each chamber render it infeasible to extract that information from the data available. |

Selected Budget and Policy Issues in H.R. 2810

Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty25

The United States and Soviet Union signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 1987. In agreeing to the INF Treaty, the United States and Soviet Union agreed that they would ban all land-based ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. The ban applies to missiles with nuclear or conventional warheads, but not to sea-based or air-launched missiles. Since 2014, the U.S. State Department has raised concerns about the Russian Federation violating the INF. In testimony before the House Armed Services Committee on March 8, 2017, General Paul Selva, the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, confirmed press reports that Russia had begun to deploy a new ground-launched cruise missile, in violation of the INF Treaty.

The House bill included a series of provisions (§§1241-1248) aimed at compliance enforcement regarding Russian violations of the INF Treaty and other related matters. The Senate bill (§1635) would have established a policy of the United States regarding actions necessary to bring the Russian Federation back into compliance with the INF Treaty. Both would have mandated that the Pentagon establish a program of record for the development of a U.S. land-based missile of INF range which, if carried out, would violate the treaty.

The final version of the bill retains the language that requires the Secretary of Defense to "establish a program of record to develop a conventional road-mobile ground-launched cruise missile system with a range of between 500 to 5,500 kilometers" and authorizes $58 million in funding for the development of active defenses to counter INF-range ground-launched missile systems; counterforce capabilities to prevent attacks from these missiles; and countervailing strike capabilities to enhance the capabilities of the United States.

|

The INF Treaty For background and analysis on the INF Treaty see CRS Report R43832, Russian Compliance with the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

Countering Russia26

Like the House and Senate versions of the bill, the final version of the NDAA includes several policy provisions aimed at countering Russian aggression and malign influence in Europe and expressing support for the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI). For example, in the enacted version of H.R. 2810

- Section 1273 requires a five-year plan of activities and resources for EDI that would be generally similar to the plan that would have been required by Section 1275 of the House version of the bill;

- Section 1205 extends existing authorities for the training of Eastern European national security forces in multilateral exercises, as would Sections 6209 and 6210 of the Senate version of the bill;

- Section 1279D authorizes the Secretary of Defense to provide joint security assistance to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to improve their interoperability and build capacity to deter aggression, while Sections 1237 and 1238 of the House bill would have expressed support for those three countries and Georgia.

- Section 1234 extends current authorities to provide security assistance—including defensive lethal assistance and intelligence support—to Ukraine, as would the House bill (§1234) and the Senate bill (§6208);

- Section 1234 also expands authorities to provide medical treatment to wounded Ukrainian soldiers and additional forms of military assistance, as would the Senate bill (§6215);

- Sections 1231 and 1232 extend existing prohibitions on funding for military-to-military cooperation with Russia and on activities that would recognize Russian sovereignty over Crimea, echoing language in the House bill (§1231) and the Senate bill (§§1241 and 1242); and

- Section 3122 extends existing prohibitions against contracts with or assistance to Russia for atomic energy defense activities, as would Section 3117 of the House bill.

|

Additional Information on the Russian Federation For more information on Russia, see CRS Report R44775, Russia: Background and U.S. Policy, by [author name scrubbed]. |

North Korean Threats27

Both the House and Senate bills both included sense of Congress provisions related to the importance of the U.S. alliance with the Republic of Korea and threats to U.S. interests and national security posed by North Korea (see §§1264, 1266, and 1270B of the House bill and §§1268 and 1269 of the Senate bill).

The House bill also would have required the President to provide a report to Congress on cooperation between the Government of Iran and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea on nuclear weapons programs, ballistic missile development, chemical and biological weapons development, and conventional weapons (§1288). The House bill also would have required an assessment and report related to the defense of Hawaii from a North Korea ballistic missile attack (§1685).

The enacted version of the bill includes sense of Congress provisions related to the importance of the U.S. alliances with the Republic of Korea and Japan, the need to strengthen deterrence capabilities in the face of North Korean aggression, and the need to encourage further defense cooperation among the allies (see §§1254 and 1255). It also requires that the President submit a strategy on North Korea, including addressing the DPRK's nuclear weapons programs, ballistic missile development, chemical and biological weapons development, and conventional weapons (§1256). Section 1257 of the conference report requires a briefing by the Secretary of Defense to the armed services committees on the "hazards or risks posed directly or indirectly by the nuclear ambitions of North Korea" including a plan to deter and defend against such threats. The NDAA conference report also adds a requirement that the annual report on the Military Power of Iran also include an assessment of military-to-military cooperation between Iran and North Korea (§1225). The conference report also requires an assessment and report related to the defense of Hawaii from a North Korea ballistic missile attack (§1680).

|

Additional Information on North Korea For additional background and information on U.S. -North Korea relations and policy options, see CRS Insight IN10734, North Korea's Long-Range Missile Test, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed], CRS In Focus IF10246, U.S.-North Korea Relations, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed], CRS In Focus IF10467, Possible U.S. Policy Approaches to North Korea, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed], and CRS In Focus IF10472, North Korea's Nuclear and Ballistic Missile Programs, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

Prohibitions on Transfer or Release of Detainees28

The final version of H.R. 2810—like the versions passed by the House and Senate—included provisions that extend until December 31, 2018, previously enacted provisions prohibiting or restricting the transfer or release of detainees at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In the final bill

- Section 1033 prohibits the use of any funds available to DOD to transfer or release Guantanamo Bay detainees to the United States, its territories, or possessions;

- Section 1034 prohibits the use of funds to construct or modify any facility in the United States to house detainees transferred from Guantanamo Bay;

- Section 1035 extends the current prohibition on the use of any funds to transfer or release detainees to Libya, Somalia, Syria, or Yemen; and

- Section 1036 prohibits the use of funds to close or relinquish U.S. control of the Guantanamo Bay base.

The Senate bill included a provision (§1035) that would have allowed the temporary transfer of a detainee to the United States for necessary medical treatment not available at Guantanamo Bay. That provision was not included in the final bill.

Selected DOD Cyber Matters29

Both the House and Senate versions of the NDAA included several provisions related to DOD-focused cybersecurity and cyberspace issues which were incorporated into the final version of the bill, with modifications.

House-Originated Provisions

In the version of H.R. 2810 originally passed by the House:

- Section 1651 would have required the Secretary of Defense to "promptly submit in writing [to Congress] notice of any sensitive military cyber operation and notice of the results of the review of any cyber capability that is intended for use as a weapon." In the final version of the bill, Section 1631 modifies the House provision to require that the legal reviews of cyber capabilities intended for a weapon be submitted on a quarterly basis in aggregate form.

- Section 1654 would have required the Secretary of Defense to develop plans to increase regional cyber planning and enhance information operations to counter information operations and propaganda by China and North Korea. A slightly modified version of that requirement is included in Section 1641 of the final version of the NDAA.

- Section 1655 would have required a report on the progress of the review of the possible termination of the dual-hat arrangement of the commander of U.S. Cyber Command, who also serves as Director of the National Security Agency. This review had been mandated by the FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328). The corresponding provision in the final version of the bill (§1648) requires that this report be informed using data from the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation, in consultation with the USCYBERCOM commander and Director of NSA.

Senate-Originated Provisions

In the version of the FY2018 NDAA originally passed by the Senate:

- Section 1621 would have established, as a policy of the United States, that the United States should "employ all instruments of national power, including the use of offensive cyber capabilities, to deter if possible, and respond when necessary, to any and all cyberattacks or other malicious cyber activities that target United States interests...." In the final version, this was replaced by Section 1633, which requires the President to develop a national policy for the United States relating to cyberspace, cybersecurity, and cyberwarfare.

- Section 1622 of the original Senate bill would have required the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the Director of National Intelligence, the Attorney General, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and the Secretary of State, to complete a cyber posture review. In the final version of the bill, Section 1644 expanded the scope of the required study to include a review of the role of cyber operations in combatant commander operational planning; a review of the relevant laws, policies, and authorities; and a review of the various approaches to cyber deterrence.

- Section 1625 would have established a Strategic Cybersecurity Program to conduct continual "red-teaming" reviews of weapon systems, offensive cyber systems, and critical infrastructure of DOD. This provision was supplanted in the final bill by Section 1640, which calls on the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the Director of the National Security Agency, to submit to the congressional defense committees a plan for carrying out the activities described in the Senate provision.

- Section 6211 of the Senate bill would have modified an existing requirement for an annual report on Russian military developments to include Russia's information warfare strategies and capabilities. In the final version of the bill Section 6212 requires a separate annual report on Russian efforts to propagandize members of the U.S. Armed Forces.

- Section 1042 of the Senate bill would have established a task force to integrate DOD organizations responsible for information operations, military deception, public affairs, electronic warfare, and cyber operations. In the final bill, Section 1042 requires the Secretary of Defense to establish processes and procedures to integrate strategic information operations and cyberenabled information operations across the responsible organizations. It also requires that a senior DOD official implement and oversee such arrangements.

- Section 902 of the Senate bill would have delineated the responsibilities of DOD's Chief Information Warfare Officer. In the final version, Section 909 requires that this official be appointed by the President subject to Senate confirmation.

A provision of the original Senate-passed version retained in the final version as Section 1649B requires an update on the federal cyber scholarship-for-service program. This program awards graduate and undergraduate scholarships to students in cyber-security-related programs in return for which recipients agree to work in cybersecurity for a federal agency or other designated entity after graduation for a period equal to the length of the scholarship.

A provision in the original Senate-passed provision (§6608) that was not included in the final version of the bill would have required a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on any critical telecommunications equipment manufactured by or incorporating information manufactured by a foreign supplier that is closely linked to a leading cyber threat actor.

Selected Government-Wide Information Technology Matters30

The Senate incorporated into its version of the NDAA the text of two previously introduced bills dealing with government-wide cybersecurity and information technology matters.

OPEN Government Act

Section 6012 of the Senate bill incorporated the "Open, Public, Electronic, and Necessary Government Data Act" or (OPEN Government Act), previously introduced as S. 760. It would require federal government agencies to catalog and publish their data in formats that are machine usable and to provide a license for open use of those data. This provision mirrored recommendations made in the Report of the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, created by P.L. 114-140.31

The final version of the NDAA did not include this provision.

MGT Act

Sections 1091-1094 of the Senate version, comprising the "Modernizing Government Technology Act of 2017," or MGT Act, were incorporated into the final version of the NDAA as Sections 1076-1078. These sections authorize the creation of working capital funds in individual agencies, and a central fund managed by the General Services Administration (GSA) to improve or replace legacy government information technology. The savings realized through modernizing the technology are to be used to replenish the fund for future use. This legislation had been introduced as S. 990 and had been passed by the House on May 17, 2017, as H.R. 2227.

Software Security Issues

The final version of the NDAA included, in modified form, two other Senate-passed provisions dealing with software security threats:

- Section 1634 of the final bill prohibits the use by any federal agency of software products developed by Kaspersky Lab, a Russian firm selling antivirus software. The Department of Homeland Security has banned the use of Kaspersky products by federal agencies because of allegations that the company is associated with Russian espionage efforts. The provision also requires a report on procedures that are to be followed to remove suspect software from federal IT systems. A similar ban on Kaspersky products had been included in the Senate bill as Section 11603.

- Section 1646 of the final bill requires a DOD report to the appropriate congressional committees on the potential offensive and defensive applications of blockchain technology and on any efforts by foreign powers, extremist organizations, or criminals to utilize those technologies. The Senate version had included a similar provision as Section 1630.

Military Personnel Matters32

Continuing the basic thrust of a congressional initiative in the FY2017 NDAA, the Administration's FY2018 budget request would sustain the currently authorized end-strength of the active-duty components of the Army and Marine Corps.33 The two services' end-strengths increased gradually in the years after 2001, but those increases accelerated between 2006 and 2010 in response to the tempo of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. The active duty end-strengths of the Army and Marine Corps peaked in 2010 and 2009, respectively, with the Army at slightly more than 566,000 and the Marine Corps at slightly less than 203,000. (See Figure 5.)

|

|

Source: Defense Manpower Data Center and FY2018 NDAA. Notes: This table includes actual end-strengths for FY2001 through FY2017 and authorized end-strength for FY2018. |

Beginning with the budget for 2012, the Obama Administration proposed—and Congress generally approved—a drawdown in the two services, with the Administration ultimately proposing an end-strength goal of 450,000 for the Army and 182,000 for the Marines.34 In the FY2017 NDAA, Congress changed that trajectory, rejecting proposals by the Obama Administration to continue the Army and Marine Corps reductions. Instead, that bill increased the Army's authorized end-strength to 476,000—an increase of 16,000 over the budget request—and increased the Marine Corps end-strength to 185,000, an increase of 3,000 over the request.

The FY2018 budget request proposed maintaining those end-strengths for the Army and Marine Corps, while increasing the Navy to 327,900 (+4,000) and the Air Force to 325,100 (+4,100).

The FY2018 request would increase the active-duty end-strength of the Armed Forces to 1,314,000, an increase of 8,100 over the FY2017 end-strength cap. By one widely used rule-of-thumb, the annual pay and benefits for each additional active-duty servicemember cost about $100,000. On that assumption, the requested end-strength increase would cost about $810 million annually.

The enacted version of the FY2018 NDAA authorized a larger number of personnel than requested for the Army (active and reserve) and the Marine Corps. Table 3 summarizes the end-strength authorizations proposed by the Administration, the end-strengths authorized in the House and Senate NDAAs, and the end-strengths enacted into law by the FY2018 NDAA (P.L. 115-91).

|

Budget Request |

House-passed |

Senate-passed |

Final bill |

|

|

Army |

476,000 |

486,000 |

481,000 |

483,500 |

|

Navy |

327,900 |

327,900 |

327,900 |

327,900 |

|

Marine Corps |

185,000 |

185,000 |

186,000 |

186,000 |

|

Air Force |

325,100 |

325,100 |

325,100 |

325,100 |

|

Total, |

1,314,000 |

1,324,000 |

1,320,000 |

1,322,500 |

|

Army National Guard |

343,000 |

347,000 |

343,500 |

343,500 |

|

Army Reserve |

199,000 |

202,000 |

199,500 |

199,500 |

|

Navy Reserve |

59,000 |

59,000 |

59,000 |

59,000 |

|

Marine Corps Reserve |

38,500 |

38,500 |

38,500 |

38,500 |

|

Air National Guard |

106,600 |

106,600 |

106,600 |

106,600 |

|

Air Force Reserve |

69,800 |

69,800 |

69,800 |

69,800 |

|

Total, |

815,900 |

822,900 |

816,900 |

816,900 |

|

Coast Guard Reserve |

7,000 |

7,000 |

7,000 |

7,000 |

Source: H.Rept. 115-200, Report of the House Armed Services Committee on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA, July 6, 2017; S.Rept. 115-125, Report of the Senate Armed Services Committee on S. 1519, the FY2018 NDAA, July 10, 2017; H.Rept. 115-404, conference report on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA.

Military Pay Raise

Title 37 of United States Code provides a permanent formula for an automatic annual increase in basic pay that is indexed to the annual increase in the Employment Cost Index (ECI) for "wages and salaries" of private industry workers.35 The FY2018 budget request proposed a 2.1% increase in basic pay for military personnel instead of the 2.4% increase that would occur automatically.

In most years from 2001 through 2010, increases in basic pay were above ECI. From 2011 through 2014, raises were equal to ECI as per the statutory formula. From 2014 through 2016, the rate of military pay raises slowed as the President invoked his authority to set an alternative pay adjustment below the ECI, and Congress did not act to overturn those decisions. In 2017 the President proposed a pay raise that was lower than the ECI, but Congress included a provision in the FY2017 NDAA that set the pay raise at the ECI rate. The FY2018 budget proposed increasing basic pay by 2.1% rather than the statutory formula of 2.4%, but in the FY2018 NDAA Congress required that the 2.4% statutory formula go into effect (see Figure 6).

|

|

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Cost Index; National Defense Authorization Acts for FY2001-FY2018. Note: This table only includes increases in basic pay applicable to all servicemembers; it does not include increases in basic pay for specified paygrades that were included in a series of "pay table reform" measures in 2000-2004, and 2007. |

Military Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment

Over the past decade, the issues of sexual assault and sexual harassment in the military have generated a good deal of congressional and media attention. In 2005, DOD issued its first department-wide sexual assault policies and procedures.36 Between 2012 and 2017, DOD took a number of steps to implement its own strategic initiatives as well as dozens of congressionally mandated actions related to sexual assault prevention and response, victim services, reporting and accountability, and military justice.37

House and Senate versions of the NDAA as well as the final version included a number of provisions aimed at expanding or clarifying existing requirements in these areas. One new departure in this area was Section 533 of the final bill (corresponding to Section 523 in the House bill and Section 532 in the Senate bill) amending the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) to criminalize wrongful broadcast or distribution of intimate visual images.

|

FY2018 NDAA Provisions Related to Military Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment For additional background and a complete list of proposed FY2018 NDAA provisions related to military sexual assault and sexual harassment see CRS Report R44923, FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]. |

Strategic Nuclear Forces38

The Trump Administration initiated a new review of the U.S. nuclear force posture in 2017 but also pledged to continue most, if not all, previously planned nuclear modernization programs. Hence, the FY2018 budget request sustained the previous Administration's plan to modernize each leg of the triad of long-range, nuclear-armed weapons over the course of the next decade.39

See Table 4 for information on the FY2018 budget request and authorization actions for selected strategic offense and long-range strike systems.

B-21 Long-Range Strike Bomber40

The budget includes $2.00 billion to continue development of the B-21 long-range bomber, which the Air Force describes as one of its top three acquisition priorities. Acquisition of the plane is slated to begin in 2023. The new bomber—like the B-2s and B-52s currently in U.S. service—could carry conventional as well as nuclear weapons. For the latter role, the budget includes $451.3 million to continue development of the Long Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO), a cruise missile that would replace the 1980s-vintage Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) currently carried by U.S. bombers. The House bill, the Senate amendment, and the final version of the bill all support the President's budget request for the B-21 bomber and the LRSO.

Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine41

The Columbia-class program, previously known as the Ohio replacement program (ORP) or SSBN(X) program, is a program to design and build a new class of 12 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) to replace the Navy's current force of 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The Navy has identified the Columbia-class program as its top priority program. The Navy wants to procure the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requested $842.9 million in advance procurement (AP) funding and $1.04 billion in research and development funding for the program. The budget also includes $1.3 billion to continue refurbishing the Trident II (or D-5) missiles that arm the submarines. The House bill, the Senate amendment, and the final version of the bill all support the President's budget request for the Columbia-class program and refurbishment of the Trident II missiles.

Land-based Ballistic Missiles42

Also requested is $216 million to continue developing a new, land-based intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), that in 2029 would begin replacing the Minuteman III missiles currently in service. The House bill, the Senate amendment, and the final version of the bill all support the President's budget request of $216 million for the new ground-based strategic deterrent.

|

Request |

House-passed |

Senate-passed |

Final bill |

||

|

Upgrades to Existing Bombersa |

Proc |

$362 |

$336 |

$328 |

$328 |

|

R&D |

$562 |

$366 |

$562 |

$562 |

|

|

B-21 Bomberb |

Proc |

– |

– |

– |

- |

|

R&D |

$2,004 |

$2,004 |

$2,004 |

$2,004 |

|

|

Long-Range Stand-Off Weapon |

Proc |

– |

– |

– |

- |

|

R&D |

$451 |

$451 |

$451 |

$451 |

|

|

Columbia-class Ballistic Missile Submarinec |

Proc |

$843 |

$843 |

$843 |

$843 |

|

R&D |

$1,042 |

$1,042 |

$1,042 |

$1,042 |

|

|

D-5 Trident II Missile Mods |

Proc |

$1,144 |

$1,144 |

$1,144 |

$1,144 |

|

R&D |

$135 |

$135 |

$135 |

$135 |

|

|

Ground-based Strategic Deterrent |

Proc |

– |

– |

– |

- |

|

R&D |

$216 |

$216 |

$216 |

$216 |

|

|

Conventional Prompt Global Striked |

Proc |

– |

– |

– |

- |

|

R&D |

$202 |

$202 |

$202 |

$202 |

|

|

Intermediate-Range Ground-Launched Cruise Missilee |

Proc |

– |

– |

– |

- |

|

R&D |

– |

– |

$65 |

$58 |

|

Source: H.Rept. 115-200, Report of the House Armed Services Committee on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA, July 6, 2017; S.Rept. 115-125, Report of the Senate Armed Services Committee on S. 1519, the FY2018 NDAA, July 10, 2017; H.Rept. 115-404, conference report on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA.

Notes:

a. CRS Report R43049, U.S. Air Force Bomber Sustainment and Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

b. CRS Report R44463, Air Force B-21 Raider Long-Range Strike Bomber, by [author name scrubbed].

c. CRS Report R41129, Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

d. CRS Report R41464, Conventional Prompt Global Strike and Long-Range Ballistic Missiles: Background and Issues, by [author name scrubbed].

e. CRS Report R43832, Russian Compliance with the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

Ballistic Missile Defense Programs43

The United States has been developing and deploying ballistic missile defenses (BMD) to defend against enemy missiles since the late 1940s. In 1983, President Reagan announced an enhanced effort for BMD. Since the start of the Reagan initiative in 1985, BMD has been a key national security interest in Congress, which has appropriated more than $200 billion for a broad range of research and development programs and deployment of BMD systems. The United States has deployed a global array of networked ground-, sea-, and space-based sensors for target detection and tracking, an extensive number of ground- and sea-based hit-to-kill (direct impact) and blast fragmentation warhead interceptors, and a global network of command, control, and battle management capabilities to link those sensors with those interceptors.

|

U.S. Missile Defense Programs For background and additional analysis see CRS In Focus IF10541, Defense Primer: Ballistic Missile Defense, by [author name scrubbed], CRS Insight IN10655, Current Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Issues, by [author name scrubbed], CRS Insight IN10734, North Korea's Long-Range Missile Test, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report RL33745, Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

The Trump Administration's initial FY2018 budget request included a total of $9.2 billion for defense against ballistic missiles, of which $7.9 billion would be allocated to the Missile Defense Agency (MDA). More than three-quarters of that total is for research and development. The budget amendment sent to Congress in November added a total of $4.0 billion to the missile defense request, three-quarters of which was for MDA. The supplemental request also added $905.0 million to the Army's request for Patriot and PAC-3 antimissile interceptors.

See Table 5 for information on the FY2018 budget request and authorization actions for selected ballistic missile defense systems.

U.S. Homeland Missile Defense

In the Administration's May budget submission, a total of $905 million was requested for the Ground-Based Mid-course Defense System (GMD) which, at the time the FY2018 budget was submitted, was projected to include 44 interceptor missiles deployed in Alaska and California by the end of 2017. These interceptors, the last of which was deployed in November 2017, are intended to destroy intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) with ranges in excess of 5,500 kilometers launched toward U.S. territory from countries such as North Korea and Iran. The original FY2018 budget request also included $823 million to develop improvements to the GMD system, including an upgraded interceptor missile and improved radar to be deployed in the mid-2020s.

Both the House and Senate bills would have authorized additional funding to expand the GMD effort and accelerate planned improvements. However, before conferees completed work on the final version of the NDAA, the Administration's November budget amendment boosted the total amounts requested to $1.5 billion for the current GMD system and $904 million for planned improvements. The final version of the NDAA authorized both increased amounts, in toto. The increased funding for the current homeland defense system includes $200 million to construct a third interceptor launch site at Fort Greely, Alaska, and $268 million for 20 interceptors to be deployed there.

The House bill (§1699F) and the Senate bill (§1653) each would have required DOD to develop a plan to significantly increase the number of deployed GMD interceptors. The final version of the bill (§1686) authorizes the Secretary of Defense to deploy 20 additional interceptors in Alaska and also authorizes MDA to develop detailed options for increasing to 104 the total number of interceptors deployed. This is one of the more substantial changes to the U.S. BMD System since 2002, when President George W. Bush withdrew the United States from the 1972 ABM Treaty and then began to deploy the GMD system in Alaska and California.

Regional Missile Defense

The Administration's initial budget included a total of $700.5 million for procurement and additional development work associated with the Terminal High-Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) system, which is intended to intercept short-, medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles. THAAD is a transportable system designed to defend troops abroad and population centers. In testing, THAAD has generally performed well by most measures, but THAAD has not operated in combat.

Both the House and Senate versions of the NDAA would have authorized an additional $318.4 million in procurement funding for THAAD. However, the November budget amendment boosted the total THAAD request to $1.3 billion. That amount is authorized by the final version of H.R. 2810.

The Army's Patriot system is the most mature BMD system. It was used in combat in the 1991 and 2003 wars against Iraq with mixed results and is fielded around the world by the United States and other countries that have purchased the system. Patriot is a mobile system designed to defend relatively small areas such as military bases and air fields. Patriot works with THAAD to provide an integrated and overlapping defense against incoming missiles in their final phase of flight.

The original FY2018 budget request included $625.9 million for the Patriot system. The House and Senate versions of the bill would have authorized substantially higher procurement amounts for Patriot—an additional $634 million in the House bill and an additional $650 million in the Senate bill. The November budget amendment closely tracked those proposed increases, requesting a total of $1.1 billion for Patriot procurement, the amount authorized by the final version of H.R. 2810.

The House bill included a provision (§1681) that would have required that acquisition and budgeting for missile defense programs be transferred from the Missile Defense Agency to the military service departments in time for presentation of the FY2020 DOD budget request. The corresponding provision of the enacted bill (§1676) deferred the transition deadline to the date of presentation of the FY2021 budget request.

|

Initial Budget |

House-passed H.R. 2810 |

Senate-passed |

Amended Budget Request |

Final Bill |

|||||||

|

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

||

|

Ground-based Missile Defense [U.S. Homeland Defense] (incl. test and construction of additional launch site) |

Proc |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

20 |

$268 |

20 |

$268 |

|

R&D |

– |

$905 |

– |

$1,278 |

– |

$927 |

– |

$1,035 |

– |

$1,035 |

|

|

Construction |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

$200 |

– |

$200 |

|

|

Improved Ground-based Missile Defense (interceptors and radar) |

Proc |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

R&D |

– |

$823 |

– |

$903 |

– |

$903 |

– |

$994 |

– |

$994 |

|

|

Aegis BMD/Aegis Ashore (incl. test) |

Proc |

34 |

$684 |

45 |

$742 |

34 |

$684 |

50 |

$876 |

50 |

$876 |

|

R&D |

– |

$1,027 |

– |

$1,120 |

– |

$1,120 |

– |

$1,039 |

– |

$1,039 |

|

|

THAAD |

Proc |

34 |

$452 |

58 |

$771 |

58 |

$771 |

84 |

$961 |

84 |

$961 |

|

R&D |

– |

$249 |

– |

$249 |

– |

$249 |

– |

$311 |

– |

$311 |

|

|

Patriot |

Proc |

93 |

$459 |

240 |

$1,093 |

240 |

$1,109 |

240 |

$1,106 |

240 |

$1,106 |

|

R&D |

– |

$169 |

– |

$169 |

– |

$259 |

– |

$259 |

– |

$259 |

|

|

Israeli Cooperative Missile Defense Programs |

Proc |

– |

$0 |

– |

$0 |

– |

$240 |

– |

$240 |

– |

$240 |

|

R&D |

– |

$105 |

– |

$613 |

– |

$374 |

– |

$374 |

– |

$374 |

|

|

Iron Dome |

Proc |

– |

$42 |

– |

$92 |

– |

$92 |

– |

$42 |

– |

$92 |

|

R&D |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

Sources: H.Rept. 115-200, Report of the House Armed Services Committee on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA, July 6, 2017; S.Rept. 115-125, Report of the Senate Armed Services Committee on S. 1519, the FY2018 NDAA, July 10, 2017; H.Rept. 115-404, conference report on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA.

|

Ballistic Missile Defense For more information on ballistic missile defense programs, see CRS In Focus IF10541, Defense Primer: Ballistic Missile Defense, by [author name scrubbed]. |

Space and Space-Based Programs and Activities44

The President's budget request included $6.9 billion to fund National Security Space activities. This includes a total of $1.9 billion to continue acquiring satellite launchers under the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program and developing a replacement for the Russian-made rocket engine used since the early 2000s in most national security space launches.45 The enacted version of the bill—like the versions earlier passed by the House and Senate—generally supported the President's budget request for space programs. (See Table 6.)

The Senate version of the NDAA included a provision (§1604) that would have prohibited the obligation of funding to maintain infrastructure, base and range support, sustainment commodities, and other activities associated with the Delta IV launch vehicle until the Secretary of the Air Force certified that the Air Force plans to launch a satellite on a Delta IV launch vehicle within three years. In its report on the bill, the Senate Armed Services Committee contended that, "[since] the Air Force no longer requires the Delta IV, the Air Force should not be responsible for the significant costs associated with maintaining the capability for the NRO [National Reconnaissance Office]."46 The NRO is the DOD agency that acquires and operates U.S. reconnaissance satellites. A slightly modified version of this provision is retained in the enacted version of the bill (§1611).

|

Request |

House-passed |

Senate-passed |

Final Bill |

||||||||||||||

|

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

||||||||||

|

Enhanced Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV)a |

Proc |

3 |

|

3 |

|

3 |

|

3 |

$1,564 |

||||||||

|

R&D |

– |

|

– |

|

– |

|

– |

$298 |

|||||||||

|

Space-Based Infra-red System, High (SBIRS High) |

Proc |

– |

|

– |

|

– |

|

– |

$1,187 |

||||||||

|

R&D |

– |

|

– |

|

– |

|

– |

$383 |

|||||||||

|

Advanced EHF Satellite |

Proc |

– |

|

– |

|

– |

|

– |

$57 |

||||||||

|

R&D |

– |

|

– |

|

– |

|

– |

$146 |

|||||||||

|

Global Positioning System III |

Proc |

– |

|

– |

|

– |

|

– |

$86 |

||||||||

|

R&D |

– |

|

– |

|

– |

|

– |

$1,018 |

|||||||||

Source: H.Rept. 115-200, Report of the House Armed Services Committee on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA, July 6, 2017; S.Rept. 115-125, Report of the Senate Armed Services Committee on S. 1519, the FY2018 NDAA, July 10, 2017; H.Rept. 115-404, conference report on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA.

Note:

a. For background on the EELV program—including information regarding concerns over U.S. reliance on the Russian-built RD-180 engine—see CRS Report R44498, National Security Space Launch at a Crossroads, by [author name scrubbed].

The House version of the bill would have created a Space Corps, independent of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, to "posture and properly focus" the military services to protect U.S. interests in space and provide combat-ready space forces (§1601). The Senate bill, on the other hand, would have prohibited the creation of any such corps independent of the existing service departments (§6605). Neither provision was included in the enacted version of the NDAA.

Section 1601 of the Senate bill would have required that the Commander of Air Force Space Command serve a term of at least six years. Section 1601 of the final version of the bill retains the six-year requirement. It also expands the authority of this officer over the organization, training, equipping, and operation of Air Force space activities and abolishes various other DOD offices that previously had some role in these activities.

Overview of Ground Vehicle Programs47

As the House and Senate versions of the FY2018 NDAA would have done, the final version of the bill accelerates the Administration's programs to modernize the Army's existing suite of armored combat vehicles: M-1 Abrams tanks, M-2 Bradley troop carriers, and Stryker light armored cars. All three types of vehicles, which are slated to remain in service beyond FY2028, are being given various upgrades including self-protection systems intended to neutralize antiarmor missiles.

Similarly, the enacted version of the bill—as the House and Senate versions would have done—accelerates the planned procurement of long-range artillery rockets and of the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) slated for use by all services as a replacement for the 1980s-vintage High Mobility Multi-purpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV).

The House and Senate versions, as well as the final version, authorized the amounts requested to continue a program to remount the Army's Paladin self-propelled artillery piece on a new tracked chassis, based on the Bradley. They also authorized continued acquisition of two new types of combat vehicles: the Army's Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), the Marine Corps' Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV).

|

Army Modernization Issues For additional background and analysis of Army modernization issues, see CRS Report R44366, National Commission on the Future of the Army (NCFA): Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

See Table 7 for information on the FY2018 budget request and authorization actions for selected ground vehicle programs.

Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV)

The Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV) is the Army's proposed replacement for the Vietnam-era M-113 personnel carriers, which are still in service in a variety of support capacities in armored brigade combat teams (ABCTs). While M-113s no longer serve as infantry fighting vehicles, five variants of the M-113 serve as command and control vehicles, general purpose vehicles, mortar carriers, and medical treatment and evacuation vehicles. The new vehicle would incorporate those capabilities on a Bradley chassis.

For FY2018, the Army requested a total of $647.4 million (base budget and OCO funds combined) to continue developing the AMPV and to procure the first 107 vehicles. The request was approved by the House and Senate bills and by the enacted version.

Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV)

The Marine Corps requested $340.5 million to continue developing and begin procurement of the Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV) to replace its 1970s-vintage amphibious assault vehicles. The service plans to field 204 wheeled vehicles (designated ACV 1.1) and then begin fielding a tracked vehicle designated ACV 1.2. As requested by the Administration, the enacted bill authorizes $340.5 million to continue development of the new vehicles and to acquire the first 26 ACV 1.1s. The House and Senate bills would have done likewise.

|

Request |

House-passed |

Senate-passed |

Final Bill |

|||||||

|

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

# |

Amt. |

|||

|

M-1 Abrams Tank (mod and upgrade) |

Proc |

56 |

$1,105 |

85 |

$1,651 |

56 |

$1,887 |

85 |

$1,651 |

|

|

R&D |

– |

$109 |

– |

$109 |

– |

$109 |

– |

$109 |

||

|

M-2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle |

Proc |

60 |

$675 |

93 |

$786 |

93 |

$786 |

93 |

$786 |

|

|

R&D |

– |

$131 |

– |

$131 |

– |

$131 |

– |

$131 |

||

|

M-109A6 Paladin self-propelled artillery |

Proc |

71 |

$772 |

71 |

$772 |

71 |

$772 |

71 |

$772 |

|

|

R&D |

– |

$47 |

– |

$47 |

– |

$47 |

– |

$47 |

||

|

Guided MLRS and HIMARS rocket artillery |

Proc |

– |

$1,125 |

– |

$1,697 |

– |

$1,700 |

– |

$1,698 |

|

|

R&D |

– |

$214 |

– |

$271 |

– |

$257 |

– |

$277 |

||

|

Stryker Combat Vehicle (new and mods) |

Proc |

– |

$98 |

– |

$623 |

– |

$793 |

– |

$623 |

|

|

R&D |

– |

$81 |

– |

$81 |

– |

$81 |

– |

$81 |

||

|

Armored Multi-Purpose Vehiclea |

Proc |